By David Jay Green

For two weeks last month my wife and I provided volunteer service in a refugee camp on the Greek island of Chios. The camp houses roughly 1,000 people mostly men, predominantly from Syria or Iraq-people who crossed the few kilometers of open sea from Turkey to the European Union member Greece. We worked for a Norwegian NGO, A Drop in the Ocean, generally helping with the serving of meals. The camp we worked at was a collection of plastic tents crowded together in what had been a moat for an old castle. There are very minimal services available to the people in the camp and during the recent heat wave the living conditions were quite difficult.

The influx of refugees, especially from the conflict in Syria has had profound impacts on the European political scene. In some sense, what we have been told unfolded in this small Greek island represents a microcosm of what occurred in Europe generally. The first waves of refugees were met with real compassion and people went out their way to help. Overtime it became apparent that there were no systems in place to move the many arrivals to other destinations and the islands became used as indefinite way stations. While the refugees are not restricted to the two camps on Chios they do not have permission to leave the island nor generally to work and establish a life. Many have been in the camps for months with no clear path to somewhere else. The Greek islanders find themselves the reluctant hosts of people whose presence is felt to absorb limited public services (Greece has not recovered from the recession coming at the end of the last decade) and who are blamed for depressing the important tourism industry. There seem few who attempt to recognize and bridge the very real, historic antipathy between the two religious communities, Muslim and Christian.

We were at our posts only a short time, we were there to work, and the language barriers severe so we did not really get to know the refugees as people, but some of their faces and some of their stories stay with me.

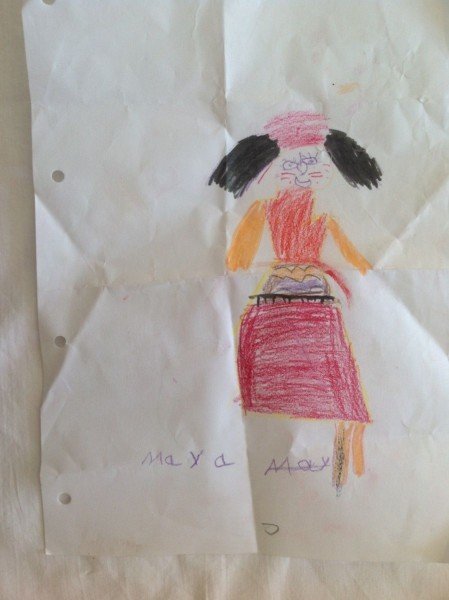

The picture that is attached to this short piece was given to me by a young girl, perhaps 6 years old, from the camp as I was helping set up the area for one of the meal distributions. She had come to recognize me and I certainly recognized her. Sometimes she was quite fun to be with, as was her sister. They could be full of energy in a manner that only a young child can be: jumping, running and loudly demanding attention. Often, however, she was quite violent, hitting out at people, especially those trying to get her out of the way of the hundreds of men who were queuing for meals. This time she seemed good, she ran up to me, gave me the picture and ran off. Not wishing to keep something perhaps she would later want I caught up with her and with a smile and some words she wouldn’t understand gave the picture back. She looked at it, threw it on the ground and again ran off. Now I’ve helped raise two children so I’m not easily discouraged by this kind of behavior. I caught up with her later and again tried to return the picture. Again she threw the picture on the ground and ran off. After another try I did give up and I’ve kept the picture.

I don’t really know this girl’s story. I don’t know even the figure in the picture, whether it was a self-portrait or a drawing of someone else. I do know that often when this little, lovely girl was having a difficult time, hitting out at me or someone else, I would look around for her parents and never saw anyone. Later I was told that the girl’s father was in Germany, her mother in the camp with her and her sister. Her mother had said that she had four children, but that two of them had been killed. I can not imagine the trauma those people have been through. In my prayers I hold the hope that those two girls and their mother find a way out of the camp to a place of safety and peace.

While the picture of the children in the camp stays vividly in my mind, most of my interaction was with the adult men that predominated. One memory is of a man I got to know as we worked what was euphemistically known as ‘crowd control’. A refugee, he was working for the Norwegian Refugee Council which was the umbrella organization for my NGO, we worked under their direction. That day the two of us were tasked with making sure that the many male refugees would peacefully queue up and not push up into the lines out of turn. Generally everything went smoothly, but sometimes the heat, the weight of serious trauma, or just the sight of a foreigner who couldn’t speak any recognizable language telling someone what to do boiled over and the pushing and shoving would start. Luckily it was usually pretty half-hearted and the situation would sort itself out.

As we were working the lines, my counterpart and I had a chance to talk. His Arabic was certainly better than mine. (I can say la or no.) His French and Italian were also pretty good and, of course, we were speaking in English. We had some things in common, both teachers in universities. Although originally from Lebanon, he had been a professor of fashion and design in a university in Damascus when the fighting broke out. He said he was caught between the two warring sides–the government saw the universities as opposition centers, the extremists equally had no room for him.

He told me that his papers had been cleared, he had permission to travel on and settle in Italy, where he had earlier studied and worked. But he wouldn’t leave the island. He had escaped Turkey at night in a small boat, coming to Chios with his nephew. While his papers were processed and cleared, his nephew’s were not and he would not leave his sister’s boy in the camp. My prayers also picture this man again being free to live and work.

In my short experience, there is no one refugee, there are people who are very different one from another and who are also refugees.

This story was originally published in Documento. Read it in Greek here

Post a comment